Last time we saw how to run some simple code on the gpu. Now let’s look at some particular aspects related to parallel programming we should be aware of. Since gpus are massively parallel processors, you’d expect you could write your kernel code for a single data piece, and by running enough copies of the kernel you’d be maximizing your device’s performance. Well, you’d be wrong! I’m going to focus on the three most obvious issues which could hamper your parallel code’s performance:

- Each of the individual cores is actually a vector processor, which means it can perform an operation on multiple numbers at a time.

- At some point the individual threads might need to write to the same position in memory (i.e. to accumulate a value). To make sure the result is correct, they need to take turns doing it, which means they spend time waiting for each other doing nothing.

- Most code is limited by memory bandwidth, not compute performance. This means that the gpu can’t get the data to the processing cores as fast as they can actually perform the computation required.

Let’s look at the vector instructions first. Let’s say you need to add a bunch of floating point numbers. You could have each core add one number at a time, but in reality you can do better. Each processing core can actually perform that addition on multiple numbers at a time (currently it is common to process the equivalent of 4 floats at a time, or a 128 bit vector). You can determine the maximum size of a vector for each type by accessing the CL_DEVICE_PREFERRED_VECTOR_WIDTH_ property for a device.

To take advantage of this feature, openCL defines types such as float4, int2 etc with overloaded math operations. Let’s take a look at a map operation implementing vectors:

__kernel void sq(__global float4 *a,

__global float *c)

{

int gid = get_global_id(0);

float4 pix = a[gid];

c[gid] = .299f * pix.x + .587f * pix.y + .114f * pix.z;

}

Full code here. A float4 just corresponds to a memory position with 4 floats next to each other. The data structure has 4 fields: x,y,z,w, which are just pointers to each of those memory positions. So if you want to create an array of floats to be processed by this code, just pack each set of 4 floats you want to access together contiguously. Interestingly, if you read float3 vectors from an array, openCL will still jump between every set of 4 floats, which means you lose one number and might result in nasty bugs. Either you leave every 4th position unused, as I did here, or you start doing your own pointer arithmetic. A small warning: if you choose to load random memory positions your memory bandwidth might suffer, because it is faster to read 32 (or some multiple) contiguous bytes at a time (if you are interested in knowing more about this topic, google memory coalescing).

This previous code was still just a map, where every computation result would be written to a different memory position. What if all threads want to write to the same memory position? OpenCL provides atomic operations, which make sure no other thread is writing to that memory position before doing it. Let’s compare a naive summation to a memory position with atomic summation:

import pyopencl as cl

import numpy as np

n_threads = 100000

N = 10

a = np.zeros(10).astype(np.int32)

ctx = cl.create_some_context()

queue = cl.CommandQueue(ctx, properties=cl.command_queue_properties.PROFILING_ENABLE)

mf = cl.mem_flags

a_buf = cl.Buffer(ctx, mf.COPY_HOST_PTR, hostbuf=a)

prg = cl.Program(ctx, """

__kernel void naive(__global int *a,

int N)

{

int gid = get_global_id(0);

int pos = gid % N;

a[pos] = a[pos] + 1;

}

__kernel void atomics(__global int *a,

int N)

{

int gid = get_global_id(0);

int pos = gid % N;

atomic_inc(a+pos);

}

""").build()

n_workers = (n_threads,)

naive_res = np.empty_like(a)

evt = prg.naive(queue, n_workers, None, a_buf, np.int32(N))

evt.wait()

print evt.profile.end - evt.profile.start

cl.enqueue_copy(queue, naive_res, a_buf)

print naive_res

a_buf = cl.Buffer(ctx, mf.COPY_HOST_PTR, hostbuf=a)

atomics_res = np.empty_like(a)

evt = prg.atomics(queue, n_workers, None, a_buf, np.int32(N))

evt.wait()

print evt.profile.end - evt.profile.start

cl.enqueue_copy(queue, atomics_res, a_buf)

print atomics_res

The first kernel runs fast, but returns the wrong result. The second kernel is way slower, but is an order of magnitude slower, because threads had to wait for each other.

1582240

[25 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 25]

31392000

[10000 10000 10000 10000 10000 10000 10000 10000 10000 10000]

There is really no better way to do concurrent writes, so you’ll have to live with the slow down if you absolutely need to do them. But often you can restructure your algorithm in such a way as to minimize the number of concurrent writes you need to do, which will speed up your code. Another way to avoid concurrency issues is to take advantage of the memory hierarchy in a gpu, which we’ll discuss next.

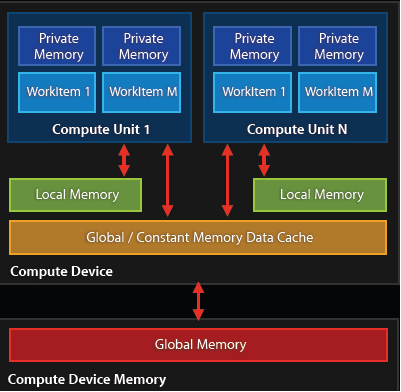

Like a cpu, there is a hierarchy of memory pools, with closer, faster pools being smaller and the off die, ‘slow memory’ being relatively large (a few GBs as of now). In openCL, these different memory spaces have the following names: private memory refers to the registers in each core, and is initialized in the kernel code itself; shared memory refers to a cache in each processing unit (which is shared by all cores within a processing unit); and global memory refers to the off die ram (there are even other memory types, but let’s stick to the basics for now).

Diagram of the memory hierarchy in a typical GPU. Credit: AMD.

In the previous code examples we’d always read and write from global memory, but every time we load something from there we will have to wait hundreds of clock cycles for it to be loaded. So it would be better if we’d load the initial data from global memory, used shared memory to store intermediate results and then store the final result back in global memory, to be read by the host. Let’s look at a program which blurs an image by dividing it into blocks, loading each block into a compute unit’s shared memory and having each core blur one specific pixel.

__kernel void blur(__global uchar4 *c,

__global uchar4 *res,

__local uchar4 *c_loc,

uint w, uint h)

{

uint xg = get_global_id(0);

uint yg = get_global_id(1);

uint xl = get_local_id(0)+1;

uint yl = get_local_id(1)+1;

uint wm = get_local_size(0)+2;

uint wl = get_local_size(0);

uint hl = get_local_size(1);

c_loc[xl+wm*yl] = c[xg+w*yg];

uint left = clamp(xg-1, (uint)0, w);

if(xl==1) c_loc[0+wm*yl] = c[left+w*yg];

uint right = clamp(xg+1, (uint)0, w);

if(xl==wl) c_loc[(wl+1)+wm*yl] = c[right+w*yg];

uint top = clamp(yg-1, (uint)0, h);

if(yl==1) c_loc[xl+wm*0] = c[xg+w*top];

uint bot = clamp(yg+1, (uint)0, h);

if(yl==hl) c_loc[xl+wm*(hl+1)] = c[xg+w*bot];

barrier(CLK_LOCAL_MEM_FENCE);

uchar4 blr = c_loc[xl+wm*(yl-1)]/(uchar)5 +

c_loc[xl-1+wm*yl]/(uchar)5 +

c_loc[xl+wm*yl]/(uchar)5 +

c_loc[xl+1+wm*yl]/(uchar)5 +

c_loc[xl+wm*(yl+1)]/(uchar)5;

res[xg+w*yg] = blr;

}

Whoa that’s a lot of lines! But they are all super simple, so let’s look at it line by line. In the function declaration you can see the __local uchar4 pointer. That points to the shared memory we are going to use. Unfortunately we cannot initialize it from the host (can only copy values to global memory) so we use lines 13-21 to read values from global memory into the local buffer, taking into account boundary conditions. In this code we distributed the threads in a 2d configuration so each thread has an id in both x and y dimensions (notice the argument for get_global_id and get_local_id denoting the dimension) so we can read off the x and y positions we want to process plus the block size directly in lines 6-12.

Once the block values have been copied to shared memory, we tell all the threads within one compute unit to wait for each other with line 22. This makes sure that everyone has loaded their corresponding values into shared memory before the code continues. It’s important to do this because each thread will read many values in the following computation. Line 23 is just the Laplace kernel which does the actual blurring. Finally we write the value back into global memory.

So how do we set up this code in pyopencl. I won’t reproduce the full code here, so let’s just look at the few important lines:

n_local = (16,12)

nn_buf = cl.LocalMemory(4*(n_local[0]+2)*(n_local[1]+2))

n_workers = (cat.size[0], cat.size[1])

prg.blur(queue, n_workers, n_local, pix_buf, pixb_buf, nn_buf, np.uint32(cat.size[0]), np.uint32(cat.size[1]))

LocalMemory is how we tell pyopencl we are going to use some shared memory in our kernel: we need to tell it how many bytes to reserve for this particular buffer. In this particular case we need block width plus two for the boundaries multiplied by block height plus boundaries, times 4 bytes for the size of a uchar4. n_workers corresponds to a tuple with the picture’s width and height, which means we launch a thread for each pixel in the image, distributed in the aforementioned 2d array. n_local corresponds to the local block size, i.e. how many threads will share a compute unit/shared memory. I encourage you to look at the full code and run it!

Next time I’ll cover some practical algorithms we can run on a gpu.