While state of the art deep learning methods can come close to human performance on several tasks (i.e. classification), we know they are not very data efficient. A human can often generalize from a single instance of a class, while deep learning models need to see thousands of examples to learn the same task. The field of few-shot classification, also known as meta learning (for supervised classification) is concerned with addressing this challenge. In this blog post I aim to give an overview of how the field has developed and where it is moving towards.

The goal is to develop a model that given some context with only a few inputs and outputs (in the case of image classification, images and their target labels) can correctly generalize to unseen data.

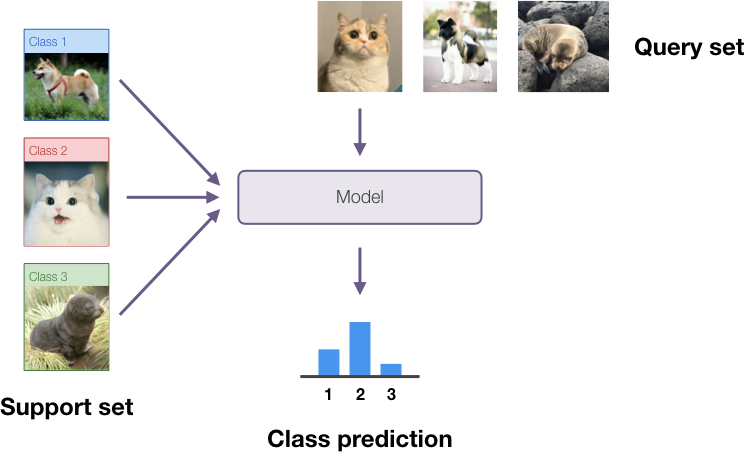

In this setting we assume we have 1 to 10 training data points per class. This amount of data is too small to realistically perform gradient descent on when a model has a very large number of parameters, and this led to the creation of a different class of methods dedicated to solving this problem. In this setting we consider the dataset to be split into two parts: the support set for which we have both inputs and outputs (target classes); and the query set for which we have only the inputs. When not using pretrained models, the training dataset is split into a number of support/query sets for training (sometimes called meta-training) and others for testing. In this case some of the classes are held out from the meta-training dataset so that there is some novelty.

Main methods for few shot classification

The most popular approaches to tackle this problem can be split into two broad categories, which I’ll outline below.

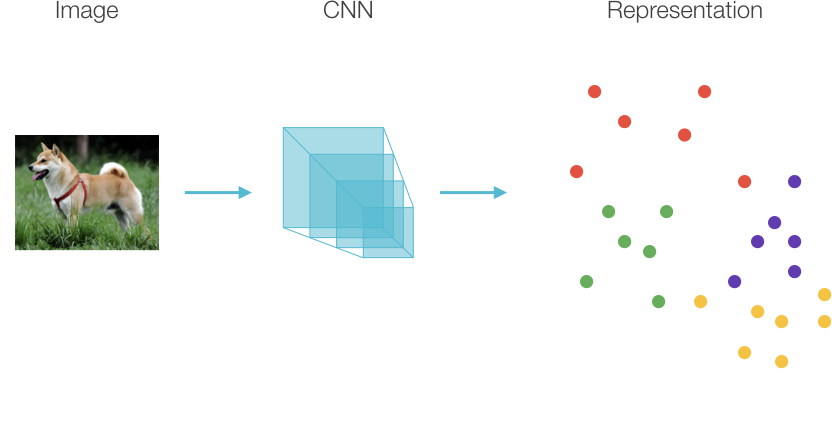

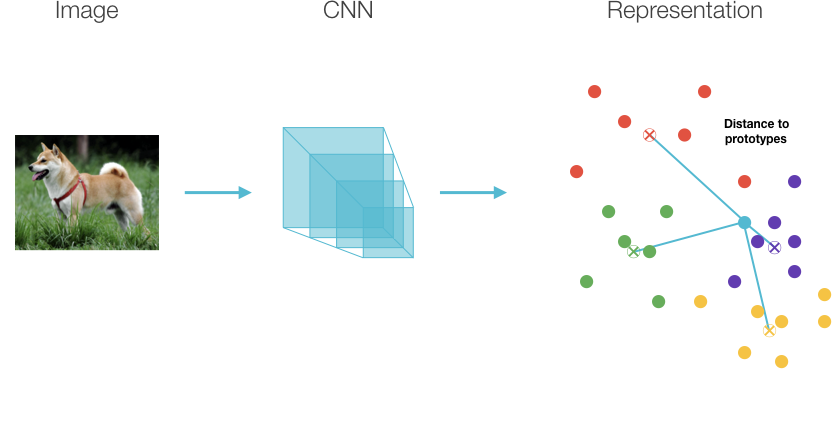

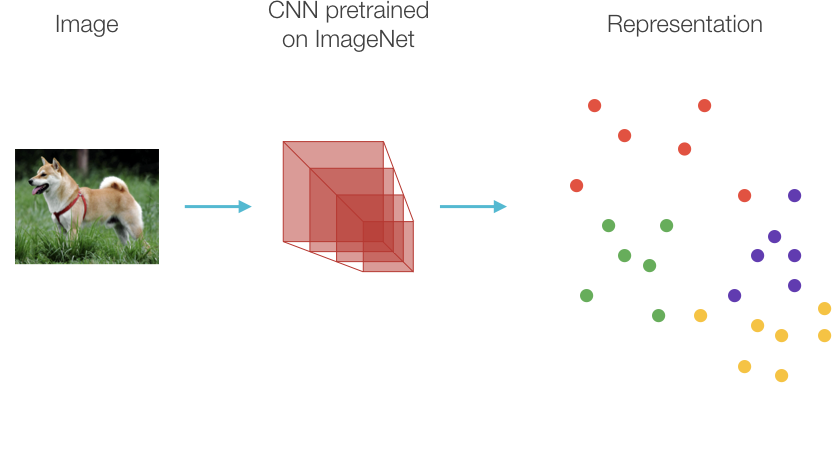

The first approach is to map the input data to a high dimensional representation space via a neural network backbone trained on other train/test data splits (in the case of image classification, often a convolutional network). On this representation space, an adaptation method can be used to split the data into different volumes corresponding to the different classes based on the support set labels.

Prototype Networks

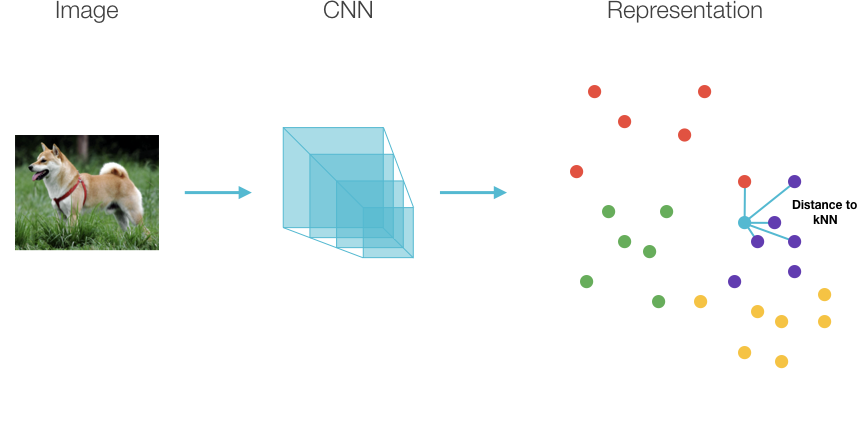

Earliest work in this branch is [Snell17] which creates clusters by averaging all representations in a given class in the support set and then uses a distance metric to calculate posterior class probabilities; and [Vinyals16] which creates a KDE estimate of the posterior class probability distribution based on the distance of the test point to its k-nearest neighbors. Performance for these methods is largely reliant on the representations created by the neural network backbone and results keep improving as bigger and deeper models are deployed.

Matching Networks

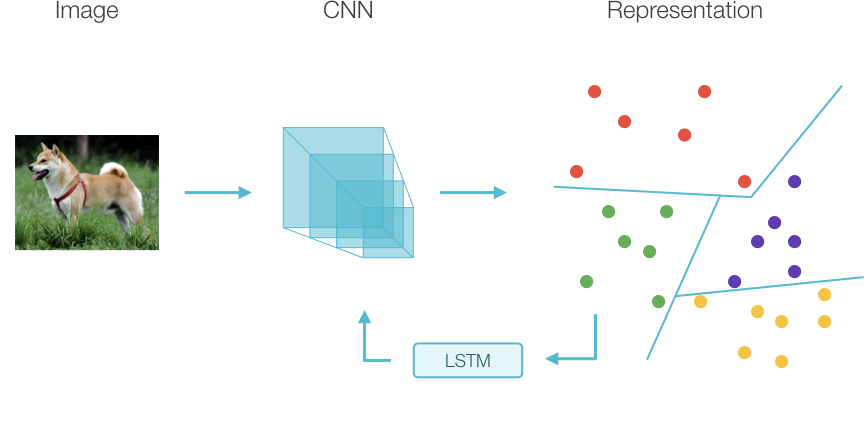

LSTM meta-learner

Another approach is to find a more efficient way to adapt the parameters of a classifier than through standard gradient descent alone. Early work [Ravi17] trained an LSTM to calculate the weight updates of a standard convolutional network, instead of using traditional gradient descent. The hope here is that the LSTM learns a good prior for what the weight updates should look like, given the query set.

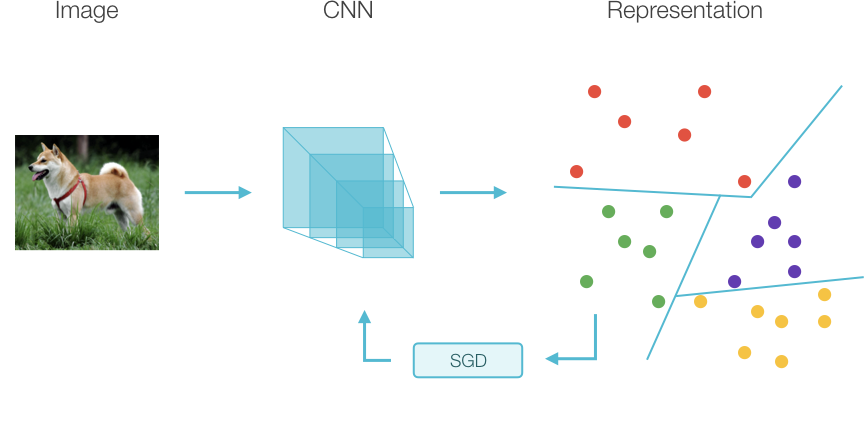

MAML

An idea with a very similar spirit was proposed in [Finn17] with MAML, one of the most popular few-shot classification algorithms currently. The authors propose training a network using two nested optimization loops: for each support/query set we have available for training, we initialize the network to the current set of parameters and perform a few steps of standard gradient descent over the cross entropy classification loss. Then we can backpropagate through that whole optimization to take one step of gradient descent over the initialization parameters to find a ‘good’ initialization with which we can get good performance after few steps of gradient descent on all train/test datasets.

A big issue with MAML is that it is computationally expensive as it requires the calculation of second derivatives, and numerous approximations have been proposed to alleviate this. Recent work [Raghu19] has shown that even for full MAML the ‘inner’ optimization loop (the few steps of vanilla gradient descent on the support set) are doing little more than changing the weights of the final classification head. The authors thus propose replacing the MAML update with fine-tuning of the final classification layer, which brings us back to the fixed representation extractor paradigm.

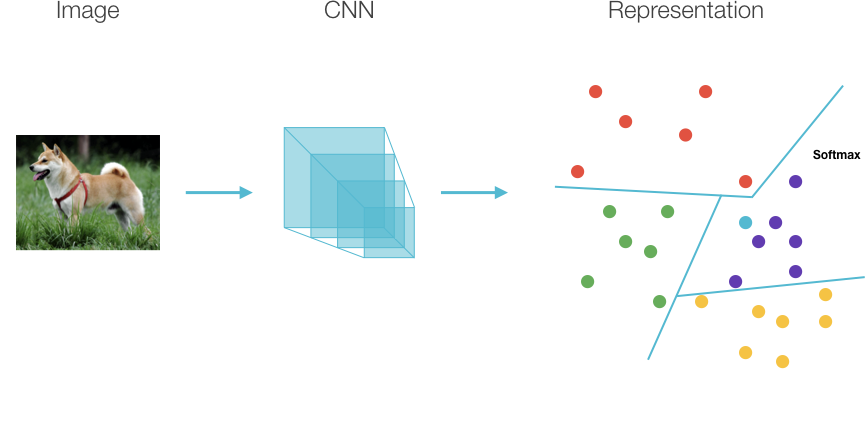

Fine-tuned classification head

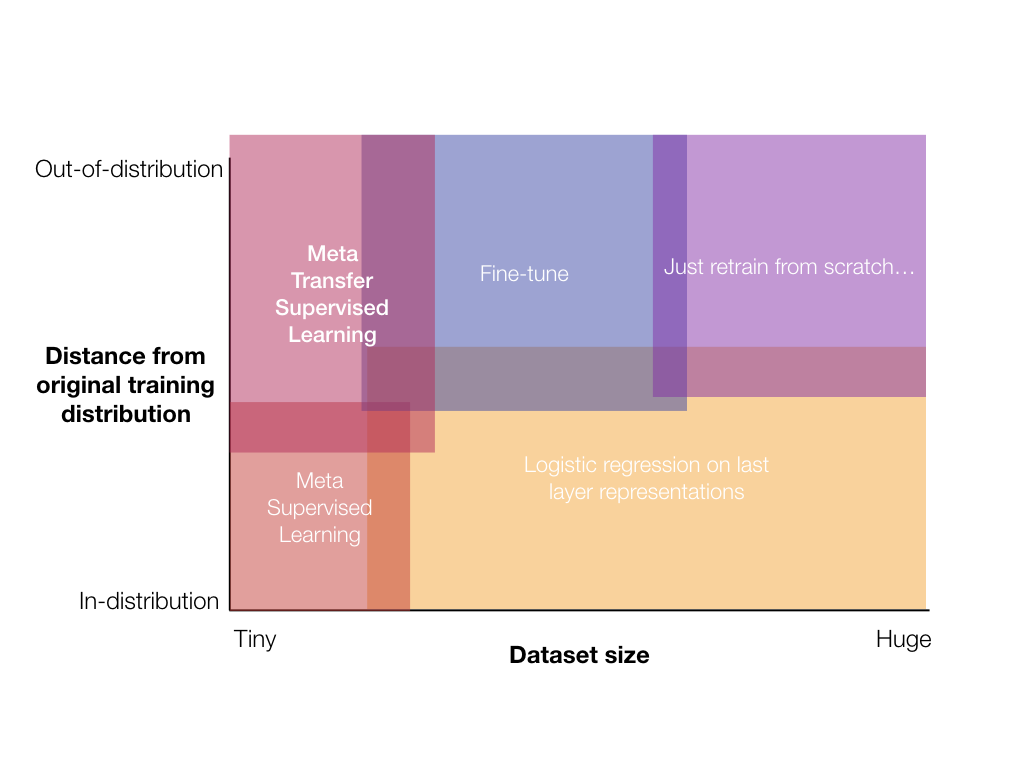

While it is never explicitly mentioned in most literature, there is a large overlap in concerns between transfer learning and few-shot learning, as recent papers have shown that to achieve good results with deep learning models in few-shot classification we have to effectively leverage some kind of prior knowledge. In the image below I summarize my current understanding of the techniques broadly applicable to a problem as a function of degree of domain transfer possible and in-domain data size.

Starting from the easiest problems, if you have a large dataset for your support set you often want to just train your model from scratch. If your dataset is significantly in-domain, you can probably get away with just retraining the classification head (i.e. logistic regression - the orange area in the schematic). Let’s quickly review transfer learning before continuing.

Transfer learning

When you have a bit less data, you can either fine-tune your whole model or just retrain the classification layer. A number of papers have investigated the tradeoffs for this scenario [Zhai19] [Kornblith18] concluding that it’s all about the representations:

- Networks pretrained on ImageNet transfer well to natural image datasets, with transfer performance positively correlated with original performance on ImageNet.

- Those networks however, transfer poorly to artificial datasets or highly fine-grained tasks, where discriminative features are probably not encoded in the networks’ representations.

- Networks trained with self-supervision seem to have a performance boost, while networks trained in a fully unsupervised way don’t really transfer well. Again this points to the original supervision signal forcing the network to encode discriminative features in the final representation.

There are significant caveats to using transfer learning with networks trained on ImageNet though. We know that their generalization power is quite brittle and very dependent on the dataset’s specific data distribution [Recht19], which could imply the representations are not as robust as we would like them to be.

A lot of recent work points towards ways to improve representation genrality such as training with adversarial robustness [Engstrom19], network architecture changes [Gilboa19], and training with more data / data augmentation [Xie19].

Transfer few-shot classification

Early work in few shot classification disregarded the transfer aspect at all. Training was performed on the meta training dataset with some classes held out, and performance was tested on remaining in-distribution held out classes. While this tests one aspect of generalization, it doesn’t tell us much about few-shot cross-domain transfer generalization. [Triantafillou19] looked at cross-domain transfer in the few-shot setting and found generally weak performance for all methods when tested on out-of-domain datasets. Training across a wider variety of datasets seems to improve performance, which hints at the fact that, again, it’s all about the representations.

In fact [Chen19] very explicitly demonstrates that few-shot classification accuracy is much more strongly correlated with backbone parameter count and depth (indirectly a proxy for representation quality) than with a specific few-shot adaptation method, and [Dhillon19] finds that even last layer fine-tuning can be competitive with few-shot classification methods when initialized properly. All this evidence points to the fact that few-shot classification is currently limited by representation generality and robustness.

In our recent work [Ramalho19] we investigate the performance of directly using CNNs pretrained on Imagenet as the feature backbone and plugging those representations into various adaptation methods. Since previous lines of research have shown that: bigger models are better, and representation quality is mostly what matters; then we want to look at what happens when we take the biggest models trained on the largest image dataset and test their transfer performance on few-shot classification tasks. The key takeaways of our investigation is as follows:

- Bigger models with better classification performance on ImageNet do perform better for few-shot classification when the tasks are not too out-of-domain (i.e. natural images, object classification tasks). If the tasks are more fine-grained, performance suffers but classification models still do well. For totally out-of-domain datasets, their performance tanks.

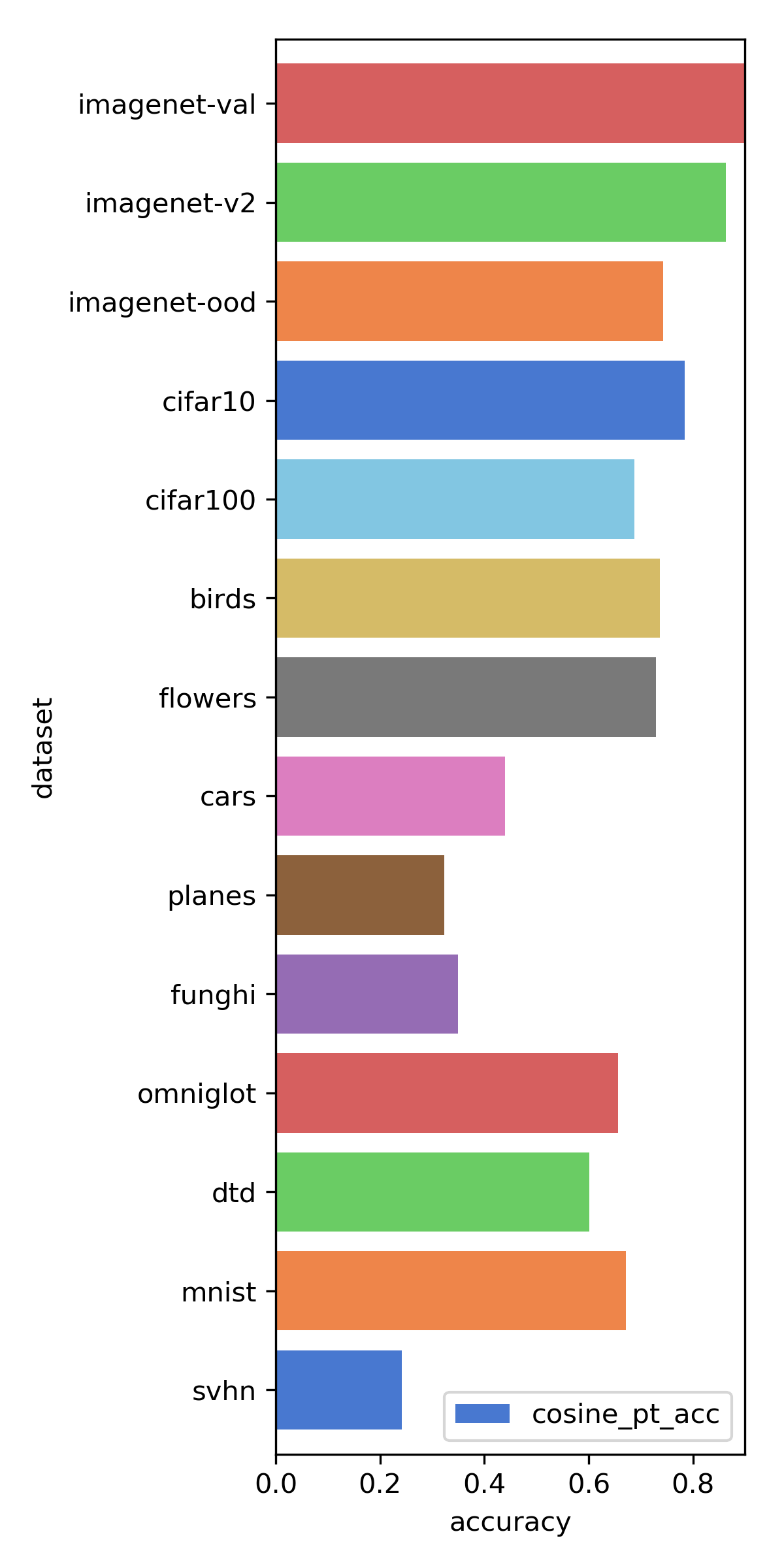

Below you can see average accuracy for EfficientNetB7 for each dataset. Fine grained classification tasks such as

cars,planes,funghi, andsvhnall could use serious improvement.

-

Unsupervised models’ representations aren’t really better even when considering cross-domain transfer. We’d hoped that these models’ representation spaces would be less overfit to the ImageNet classification task and therefore transfer better, but that does not seem to be the case.

-

Models trained with robustness transfer a bit better, but not enough to really matter.

-

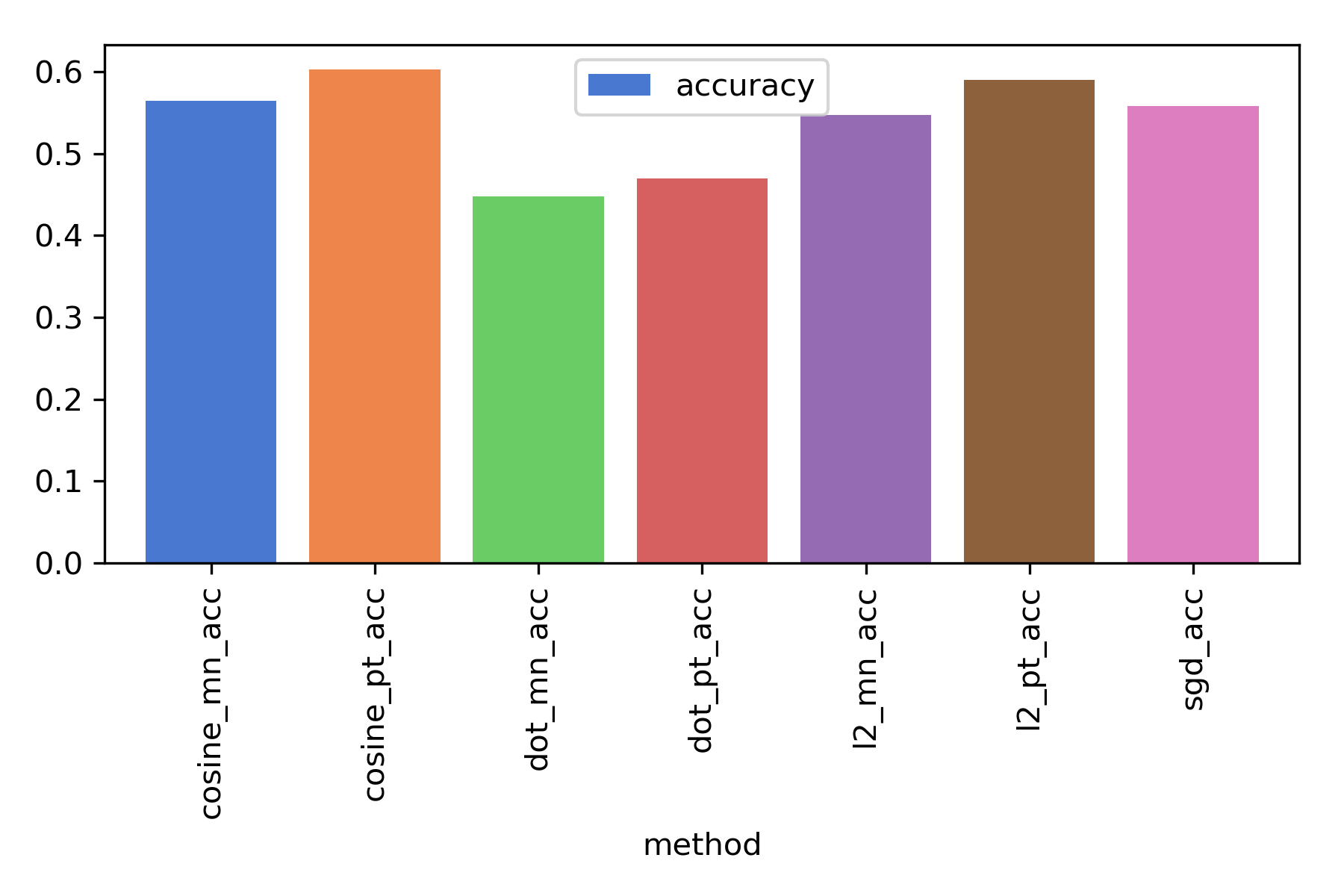

Prototype networks work for the backbones we tested. And best if we choose cosine distance instead of euclidean (models originally trained with a softmax classification objective try to maximize the dot product between the vector corresponding to a specific class and the representation of the current point, which induces a specific geometry in representation space better captured by cosine distance). Below I plotted the average accuracy over all datasets and all backbones for 5 shots classification. You can see that Prototype Networks is slightly better than Matching Networks for all distance functions, and cosine distance is better than L2 and dot product.

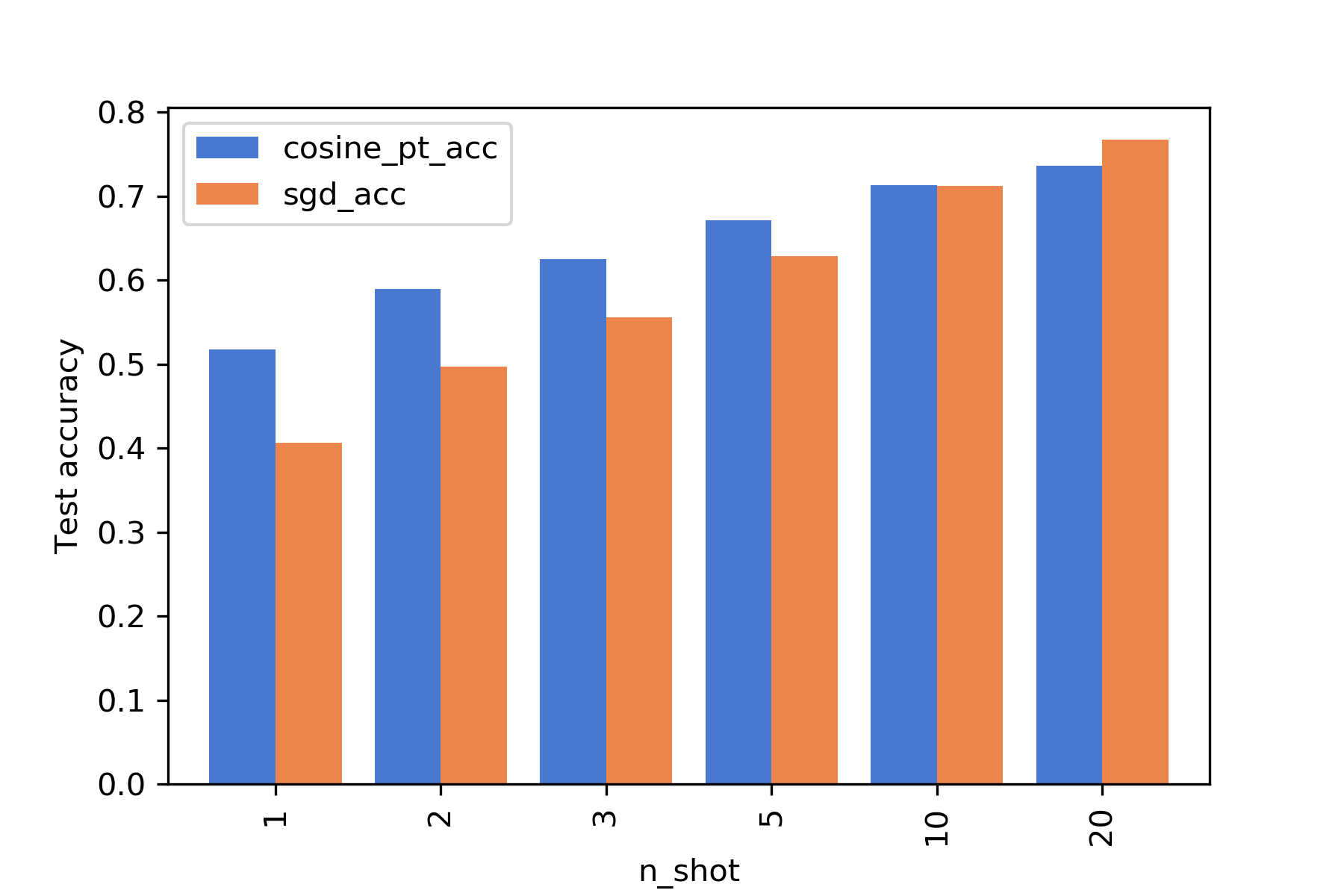

- For 10 samples and above, just finetune the classification layer instead of using few-shot classification methods! You can see a summary of the accuracy as a function of number of shots below comparing Prototype Networks with Logistic Regression with SGD on the last layer (for the EfficientNetB7 backbone).