Transformer based language models have achieved groundbreaking performance in almost all NLP tasks. So it is natural to think they can be used to improve textual search systems and information retrieval in general. Unlike what you may think, information retrieval is far from a solved problem. Suppose a query that’s simple for a human to understand:

how do crows find their way around

You’d expect to find a page such as “How do birds navigate?”, but actually Google will return the page “Frequently Asked Questions about crows”, which doesn’t really answer the question because it prioritized the word ‘crows’ over the semantic meaning of ‘how do birds find their way around’.

Consider another example:

who was the coach of the team that won the NBA in 2014

As of the writing of this post Google returns “Steve Kerr” as the answer because his wikipedia page mentions NBA and 2014 a number of times. Retrieving the answer to this question requires solving sub-problems such as “team that won the NBA in 2014”, and “The San Antonio Spurs coach”, which correctly returns “Gregg Popovich”.

To solve these questions we need to go beyond keyword matching and use methods that can match documents based on the semantics of a question, not just its words. In this post I will survey the literature of the past few years and explain a few of the methods I find most promising.

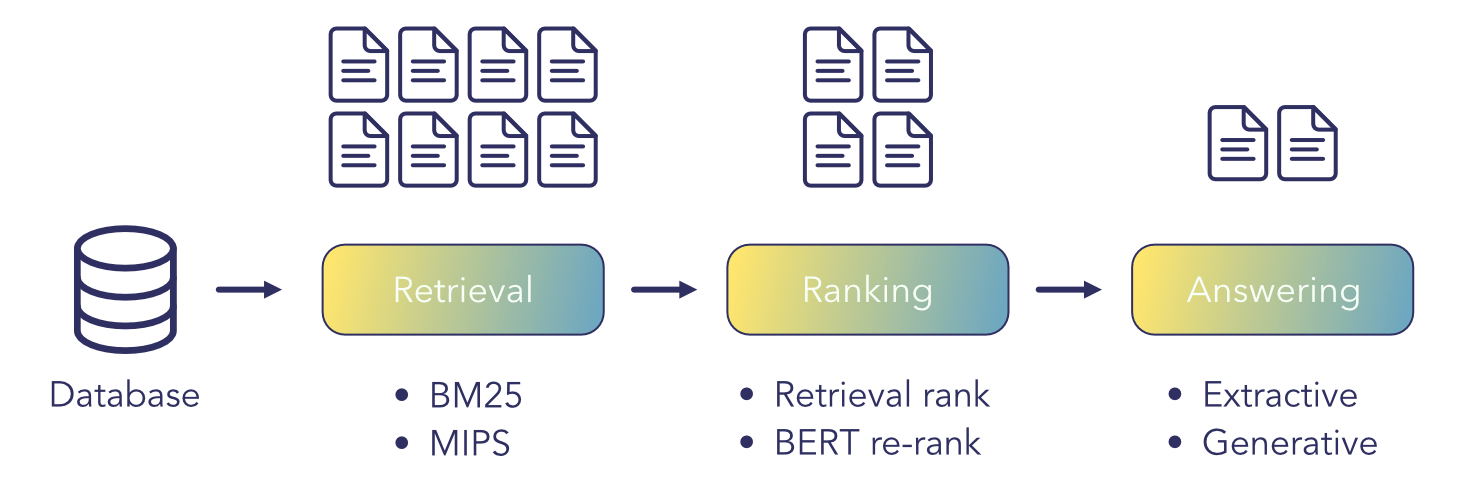

Information retrieval pipeline

In very simple terms the information retrieval (IR) problem consists of the following: assume we have a database containing a large pool of documents, and a query written by a user wishing to find some information contained in one or more of the documents in that pool. Can we help the user find that information as fast as possible?

As outlined in the image above, the pipeline for information retrieval consists of one or more methods that basically sieve the documents in the pool, retaining fewer and fewer until we show the user only a small number of documents (or answers generated from the documents) directly related to the query.

Retrieval

The retrieval step is the the most essential in any pipeline. This method should be computationally very cheap and scalable, as the full document pool can contain millions or billions of documents, and we need to return a manageable subset of documents that can be either directly returned to the user in the case of the simplest IR pipeline; or passed on to a more computationally expensive method for further processing.

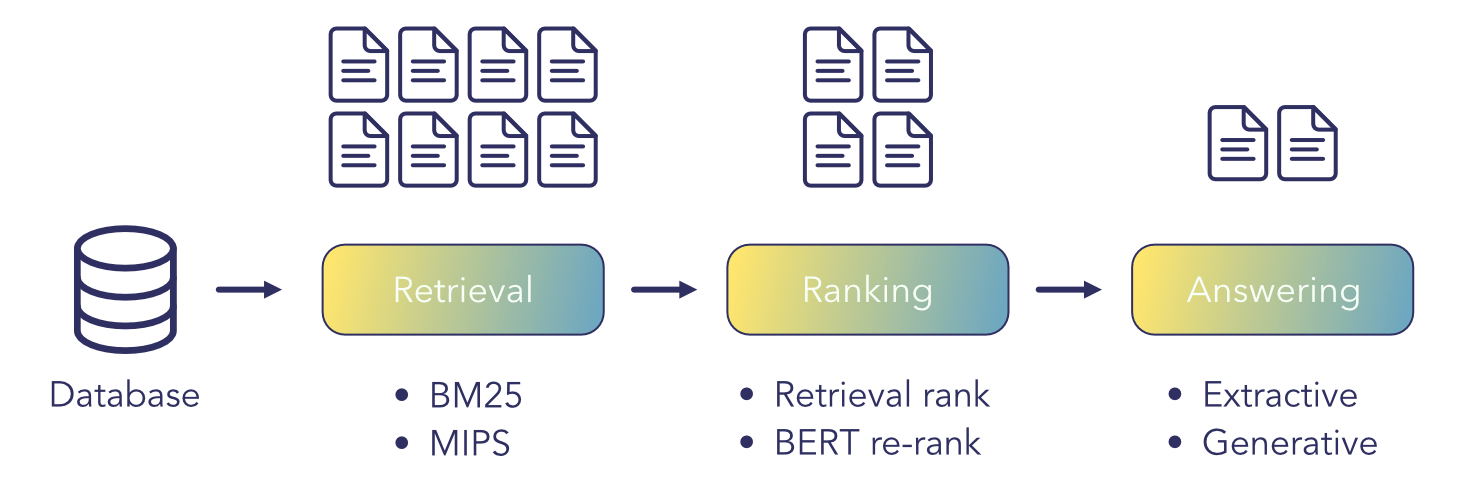

Keyword-based methods

The method that is employed by all popular search engines (such as ElasticSearch or Solr) is a variation of TF-IDF, called BM25. What both these methods do is to assign to each document a sparse vector with huge dimensionality (as many dimensions as there are words in the whole document corpus). Almost all dimensions in this vector will be 0, except ones corresponding to words that actually occur in the document. The numbers in those dimensions are proportional to how frequent that word appears in the document (term frequency, TF) and inversely proportional to how often it appears in the whole corpus (IDF, inverse document frequency). This will weight words that appear a lot in one document, but not in the whole corpus (e.g. the word “the” should not really be relevant).

We can calculate the same vector to describe the query, and then use method optimized for sparse matrices to calculate the cosine distance between the query and all the vectors describing the documents in the database. We can then keep only the top-k results.

This method is computationally very efficient but you can see that the order of the words in a document is completely lost in the transition to the sparse vector (why these methods are called bag-of-words). By extension, the meaning is largely lost. A trick to encode more meaning in this vector is to take n-grams as individual words, which helps retrieval at the cost of a much larger vocabulary. Going beyond 3-grams is not really practical.

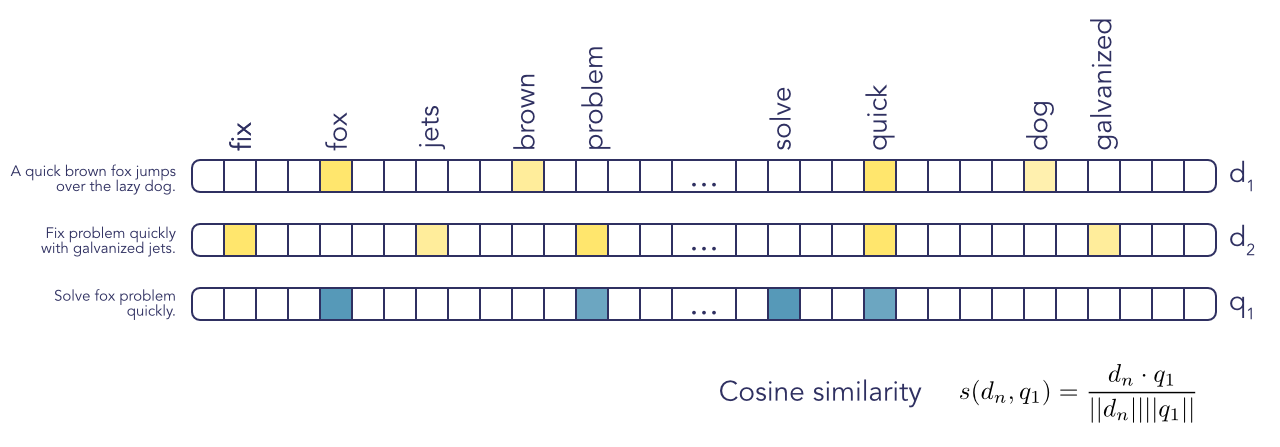

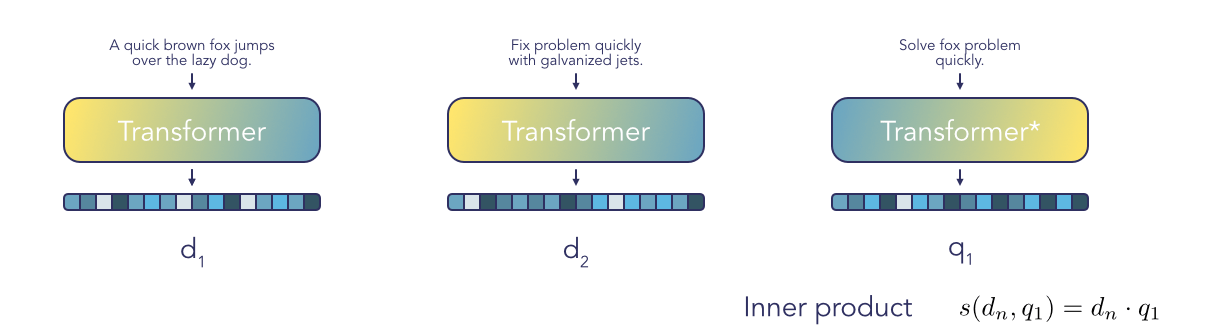

Dense vector embeddings

To capture more of the semantics, we can use Transformer models to calculate dense vector embeddings that describe more of the semantics of the documents. Practically, we split the documents into chunks that fit into the transformer context size (most models can see up to 512 tokens), and store those embeddings into a database that allows for fast-knn search such as FAISS. These embeddings can be learned either in an unsupervised way (Logeswaran et al.), or by learning to match query embeddings with relevant passages (Karpukhin et al., Ma et al.).

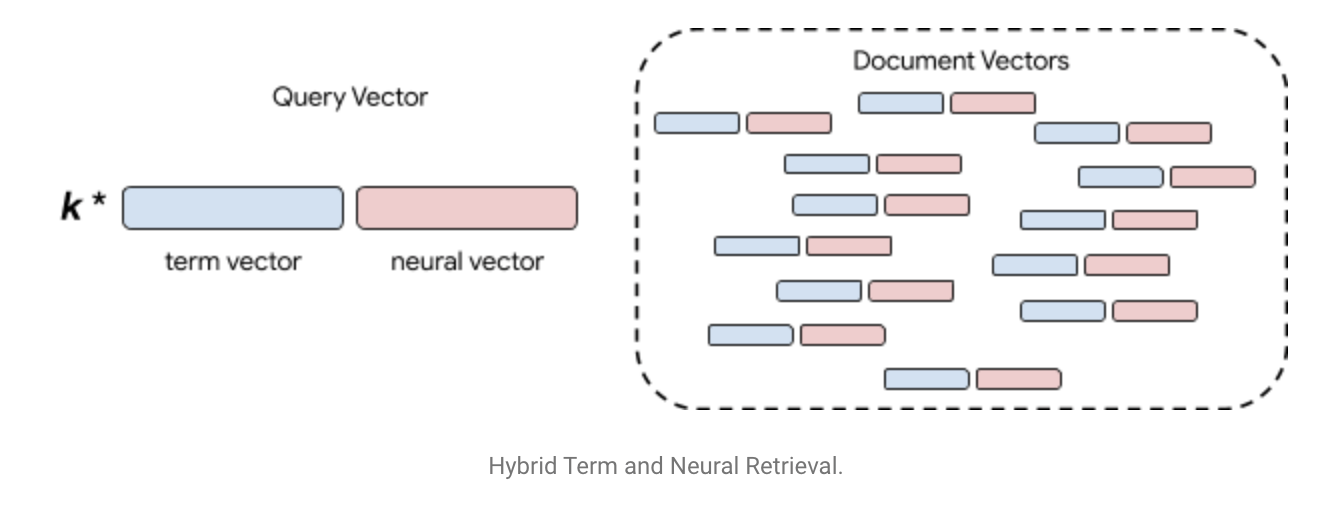

Using this method, we obtain much better generalization to documents that have similar semantic meaning. The downside of this method is that we might see unintended over-generalization in some cases: e.g. we search for good holiday spots near Barcelona but we get documents talking about good holiday spots near Marseilles. In this blog post, Google researchers proposed a hybrid method which should alleviate some of those issues.

Datasets

Both Retrieval as well as Ranking and Answering models below usually need to be trained on datasets with [query, relevant passage] pairs. Luckily recently the big tech companies have published a few large scale datasets that allow us to train these models without overfitting. Some of the datasets are more geared towards search, while others toward question answering. However, for the purposes of training the models discussed here all these datasets can be used provided the data is appropriately transformed. Here are a few pointers:

- MSMARCO - millions of query and associated relevant passage mined from the Bing search engine. Also contains a lot of negatives. Data is a bit noisy, but can’t be matched in terms of scale.

- Google natural questions - Questions and relevant passage annotated from wikipedia pages. Contains a long answer as well as short answer, if applicable.

- Google tydiqa - Similar to natural questions but multilingual. Smaller. Can be very useful if you pretrain in english and fine-tune to another language. Other small multilingual datasets are xquad and mlqa.

- Squad - The first large-scale QA dataset, still of a relevant size for modern applications.

- HotpotQA - More challenging QA dataset, with questions that require indirect reasoning.

An interesting paper to read in this area is Ma et al. which learns to generate questions given an unannotated corpus. This could be useful for fine-tuning models to more specialized domains.

Ranking

Once we have a reasonable set of relevant passages, we need to decide in which order they will be shown to the user (ideally the most relevant document should be the first to be shown to the user). The most obvious way of doing this is to directly use the score used to calculate the top-k documents in the retrieval step to rank the passages.

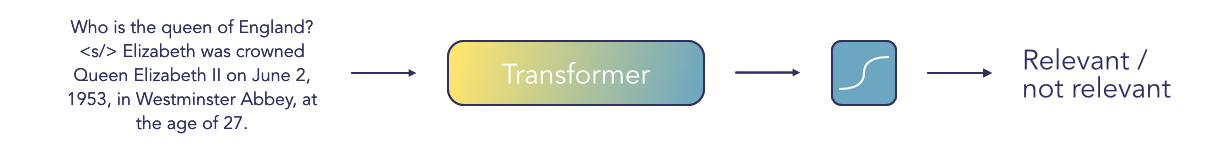

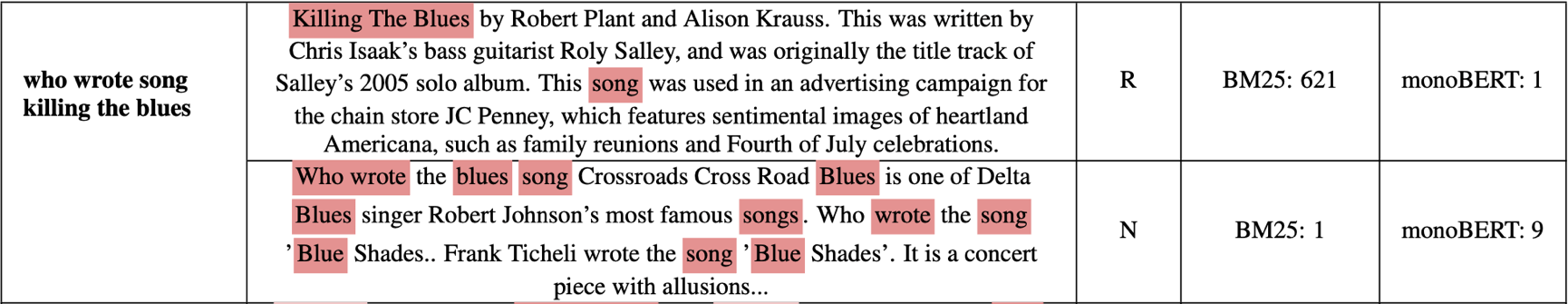

However, since we now have a much smaller set of documents (usually 10~1000), we can can try using a more computationally heavy model to re-rank them. The most basic approach is described in Nogueira et al. Again we are using a transformer model to, this time, look at the concatenated [query, relevant passage] text and predict whether this is a relevant pair or not. Compared to the transformer based retrieval method above which calculated static embeddings for each document, here the model can modulate its attention based on the query, which should give it more discriminative power.

Answering

Finally, if possible, we can extract the desired information directly from the document and present it directly to the user.

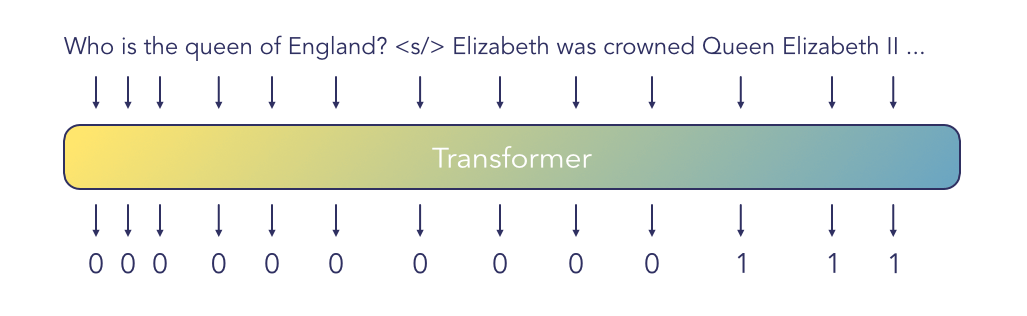

To do so, we feed the relevant passages to a model that can figure out the exact text that corresponds to the answer. There are two main approaches to this: extractive and generative. As the name implies, the former involves extracting the smallest text string that contains the answer. We do this by asking a model to predict a mask for the sequence consisting of question and passage concatenated. The text falling under the mask can then be cut and displayed. An early paper proposing a full pipeline with retrieval and extractive question answering is Chen et al.

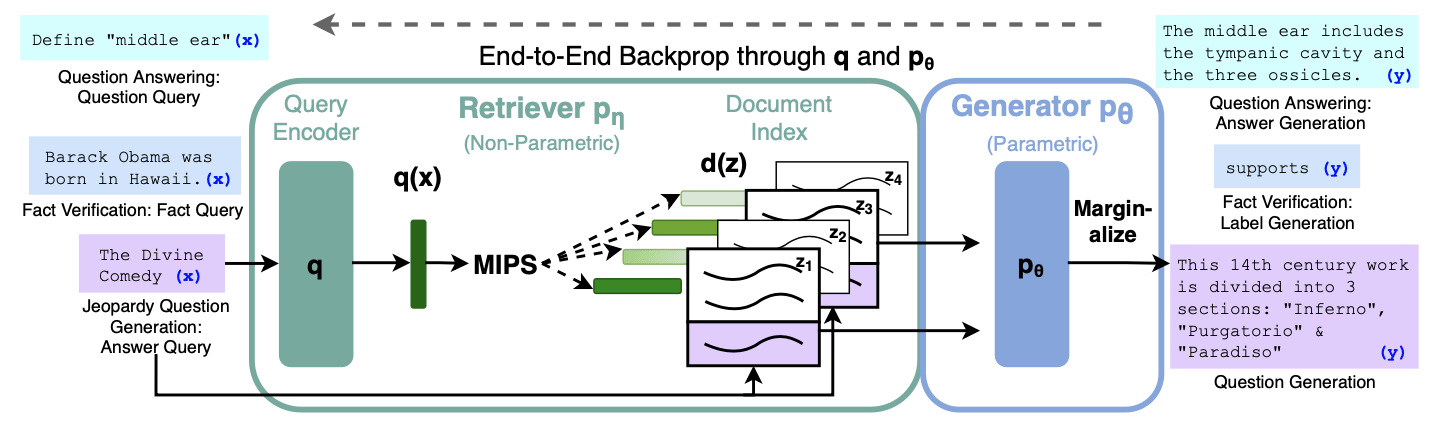

For the generative approach, we want to generate a full answer conditional on the query - passage input. This is much more difficult as we require a gold answer as well as the retrieved information. MSMARCO contains one such dataset (Natural language generation). Lewis et al. is a recent paper that tries to solve this approach with a transformer decoder paired with a dense vector space search.

Multi-hop QA

For the more challenging questions which require solving sub-problems we might require multiple database queries. This is much more challenging as the model needs to learn to emit new queries, and it’s difficult to backpropagate through that process. This area is still in its early days but I particularly liked two attempts at this.

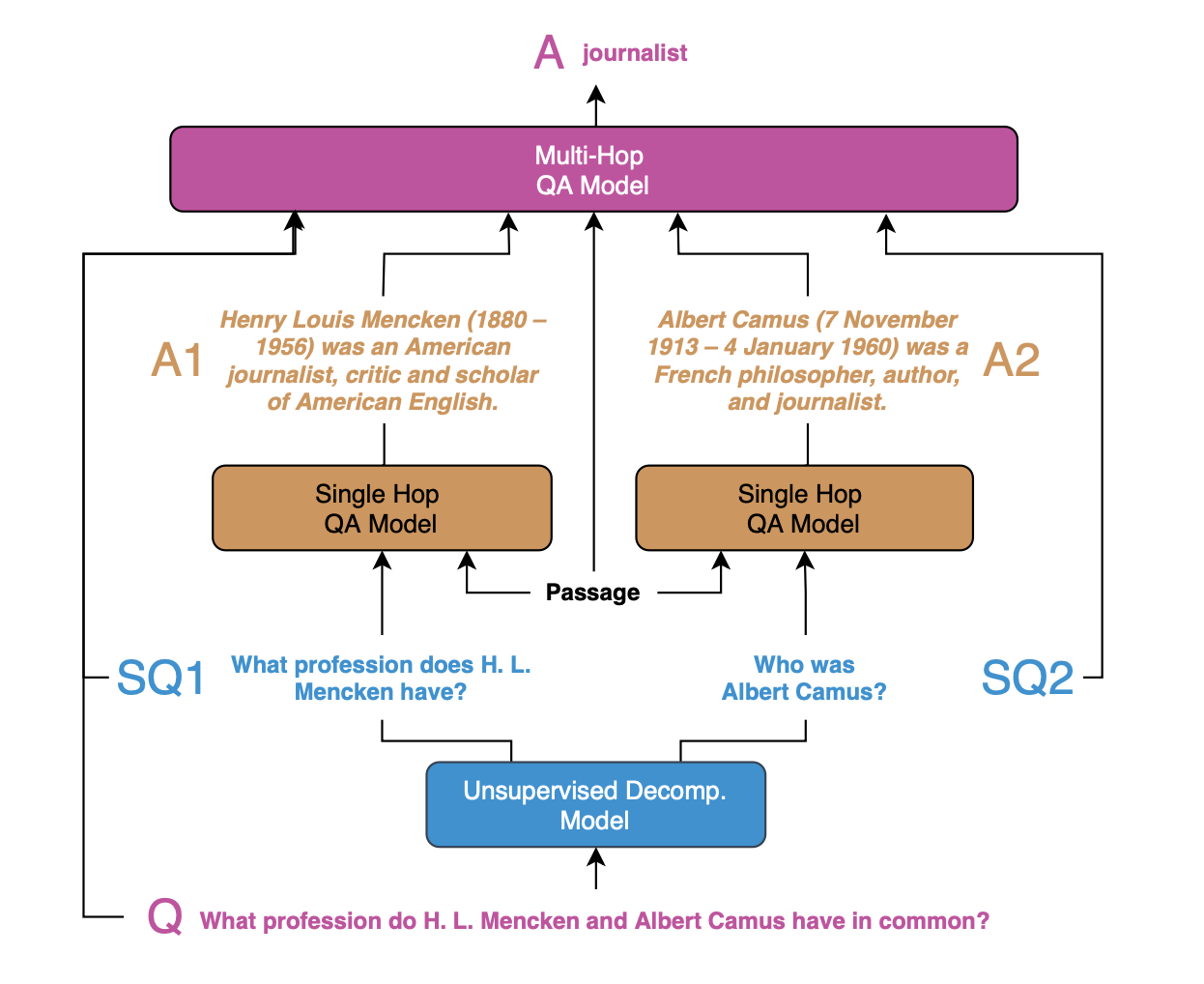

Perez et al. describe a system to learn to decompose these complex queries in an unsupervised manner. A generative model is trained to generate simple queries based on more complex questions by mining Common Crawl (a huge web dataset) for related questions. That model can then be used at inference time to provide simple queries to a simpler retrieval system, and a final answer generation model can integrate all the information to answer the question.

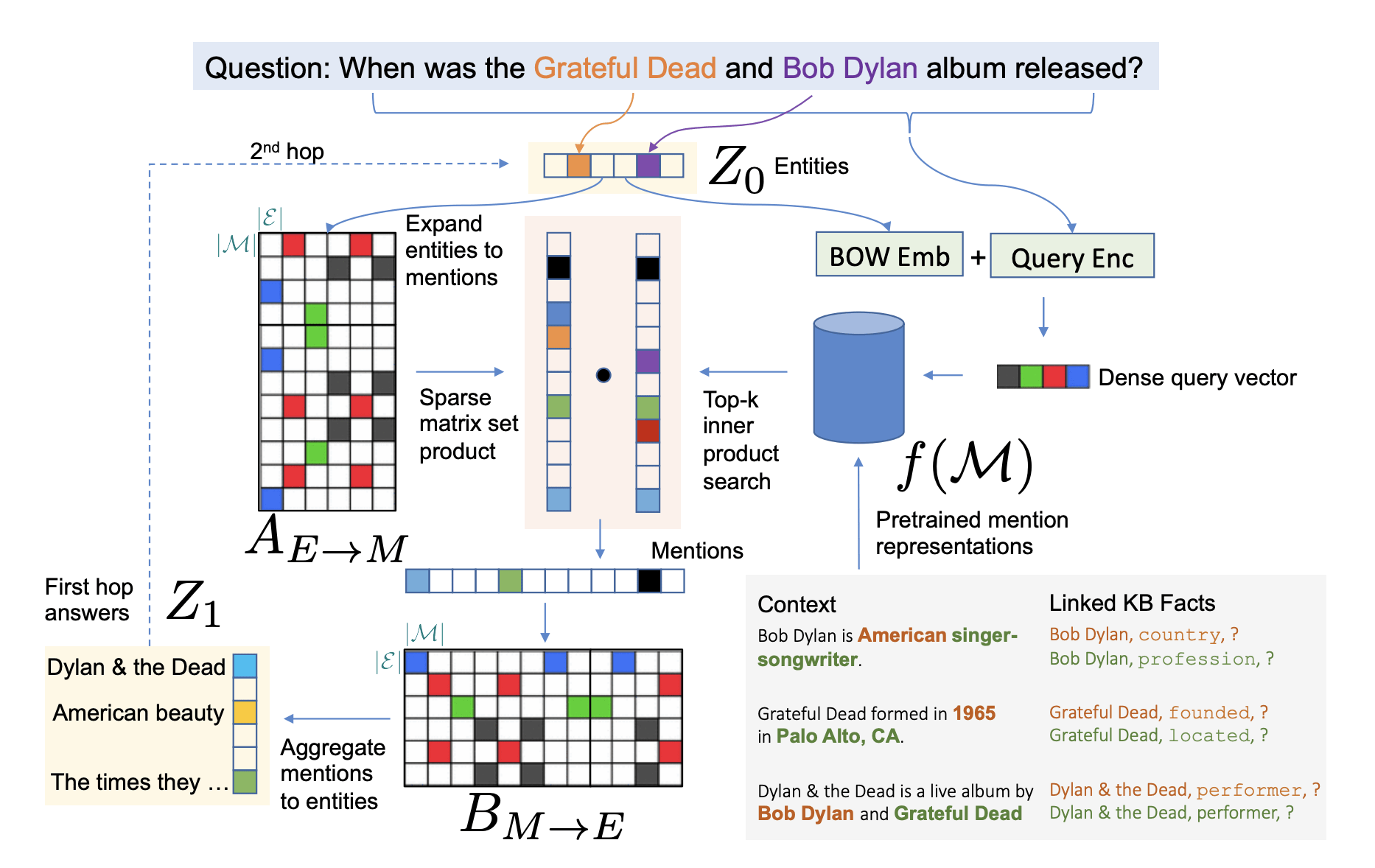

Dhingra et al. describe a hybrid TF-IDF and transformer solution. They encode the query as well as the documents into sparse vectors of “entities” (which in their case are all unigrams and bigrams in the text). We can then retrieve the top-k vectors according to TF-IDF (sparse matrix set product in the image), and pass those to a transformer that decides which new entities from the retrieved documents are relevant for the next “hop”. Those can then be used to build a new query etc. A difficulty in this method is that the entity representations need to be pretrained using an external knowledge base, which adds another step to an already complicated method.

Overall I am excited to see where this field of research goes in the coming year. This is currently where information retrieval systems are being pushed to their limits, and so we’re likely to see much more innovation in this area.

Wrap up

When I started looking into information retrieval I thought this was a largely solved problem (we have google, don’t we?). But it turns out that queries can be made arbitrarily complex, allowing us to test models’ generalisation abilities and common sense priors as far as we want. It’s a challenging application of progress in NLP modelling and exciting times to follow the literature!

Questions? Reach out to me on twitter @tmramalho.